From spears to gillnets and artisanal fishers to commercial boats, coral reef ecosystems are exploited across a range of fishing pressures and with diverse gear types. Reefs are valuable food resources for tropical coastal communities and yet our understanding of fishing impacts on reefs is often founded on studies that measure how much fish biomass is depleted in fished areas. In order to understand broader impacts on aspects of community structure we quantified reef fish size structure - the fish size distribution, or relative abundance of different body sizes - at major Pacific island groups that span gradients in human presence and environmental influences.

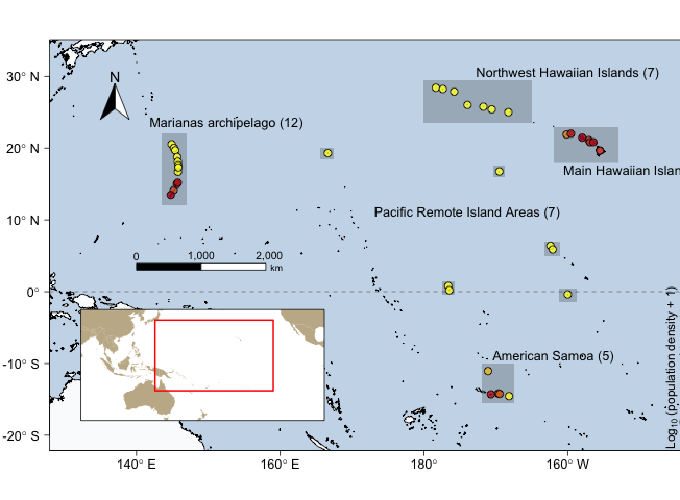

Using data collected by the Coral Reef Ecosystem Programme (NOAA), we measured the size spectrum, the large fish indicator, and total fish biomass at 38 US-affiliated islands and atolls in the Pacific Ocean, ranging from uninhabited pristine reefs (such as Palmyra atoll) to large population centres (such as Honolulu on Oahu).

The size spectrum is the exponent of the power law distribution of individual body sizes, and may be more widely recognised as the slope of the relationship between abundance ~ body size in log-log space [more information on fitting size spectra here]. The large fish indicator represents the biomass of large fishes relative to total fish biomass, and total fish biomass is the total mass of the fish community. We examined variation in these indicators across human population density, proximity to market centre, sea surface temperature, oceanic productivity, and 5 habitat variables.

Our results revealed that reef fish community size structure was degraded (or ‘steepened’) as human presence increased (Figure 1), consistent with a depletion of large-bodied fishes and a gradual shift to a communities that are dominated by small fishes. Although reef fish biomass was also depleted at high levels of human presence, all fished islands supported low biomass levels (~ 500 kg per hectare) irrespective of fishing pressure. Light size-selective fishing had a disproportionate impact on fish biomass but caused gradual shifts in size structure, and size spectra were also generally more robust to environmental variation than was fish biomass.

Change in size spectrum exponent and reef fish biomass along proximity to market (a, c) and human population density (b, d)

By shifting to greater dominance of small-bodied fishes, size-selective fishing produces fish communities that have faster biomass turnover times, greater vulnerability to environmental change, and depleted numbers of functionally important large-bodied individuals, such as the large grazing fish that control algal cover and large predatory fish that link pelagic food webs with the reef benthos. Size-selective exploitation has a consistent impact across marine ecosystems: the steepening spectra we describe here have also been widely documented in temperate fisheries . Such size-based indicators are robust and meaningful indicators of fishing pressure, and may be particularly effective for reef fisheries that often lack meaningful catch and effort data.

Future application of size-based indicators to coral reef fish communities could provide valuable insights for reef fisheries managers: for those interested in fitting size spectra or using our statistical modelling approach, here’s our R code and the study.